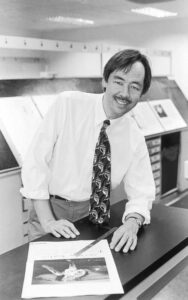

Henry Fuhrmann

By Jenna Wang, JCamp Class of 2021

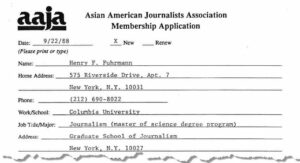

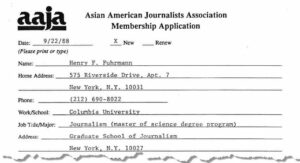

IOWA CITY, Iowa — The Asian American Journalist Association had only been in existence for seven years when Henry Fuhrmann, a 31-year old Columbia grad student studying journalism, submitted his first application for membership at the price of $18. What he didn’t know at the moment was how large an impact AAJA would have on his career and relationships in his more than three decades as a member.

The annual conventions in particular played a large social role throughout his development as a journalist.

The annual conventions in particular played a large social role throughout his development as a journalist.

“Any AAJA history that doesn’t include the word ‘fun’ is missing out on some of it,” Fuhrmann said.

For him, mostof the fun came from strong relationships he built at the conventions, such as with the AAJA founders, that lasted for decades.

“It’s a social event but it’s an empowerment event,” Fuhrmann said.

Being in a room with hundreds of other AAPI people was not a common occurrence for Furhmann, whose path to journalism was as winding as it was unpredictable. Coming out of high school, he hadn’t even considered journalism. Instead, he dove headfirst into engineering because he loved math and calculus at the time.

Yet in college, Fuhrmann struggled to find his footing. Disillusioned by the thought of solving engineering problems for the rest of his life, he didn’t know where he belonged. All he knew was that his passions were pointing elsewhere, he said.

“People always think I’m being modest, but this is the literal truth — I was really bad at engineering,” Fuhrmann said.

By a stroke of sheer luck, as he tells it, Fuhrmann met someone who would forever change the trajectory of his career. It was his new roommate that introduced him to the editor of the campus newspaper. That’s when Fuhrmann “kind of got the bug.”

He joined a group of “unwashed” engineering students who got together to put a newspaper in the 1970s. The group spent their days in computer-less rooms cutting out type in columns and sticking them to thin boards. Although the paper “wasn’t that good,” Fuhrmann knew that he had finally found what he was looking for.

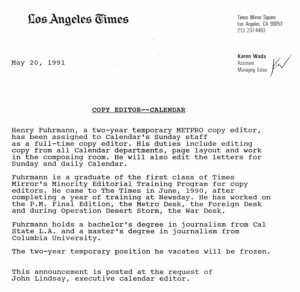

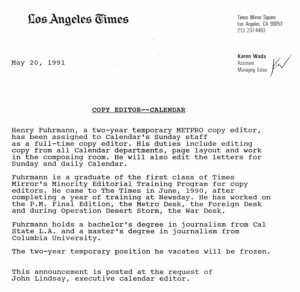

After obtaining his bachelors in journalism, his landlord who also happened to be the director of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., helped him land his first job in journalism as a science writer. Once Fuhrmann got his masters in journalism, he was then recruited to Newsday in New York City as a member of the first class of copy editors in Times Mirror’s Minority Editorial Training Program, which focused on training young journalists of color. It was the breakthrough that Fuhrmann needed.

He put his newly gained copy editing skills to use as a copy editor, news editor, and eventually rose to managing editor of the Los Angeles Times in 1990. It was at the prestigious paper where the self-proclaimed late bloomer became close with three of AAJA’s six founders.

He put his newly gained copy editing skills to use as a copy editor, news editor, and eventually rose to managing editor of the Los Angeles Times in 1990. It was at the prestigious paper where the self-proclaimed late bloomer became close with three of AAJA’s six founders.

“It’s a collaborative effort and that to me is the beauty of journalism,” Fuhrmann said. “You are collaborating with other smart, driven, energetic, passionate people.”

Through AAJA, Fuhrmann met Catalyst alumnus Karen Yin, who offered him the opportunity to write a piece in her website, Conscious Style Guide. The platform was devoted to helping writers and editors think critically about language. Fuhrmann penned a piece arguing that the hyphen in “Asian-American” should be removed from style guides because it conveyed that people of color were “not full citizens or fully American.”

Fuhrmann thought “no one would read it,” until his piece began garnering major attention across various digital media and news. It wasn’t long until Buzzfeed, the Associated Press, and The New York Times all decided to unhyphenate “Asian American” in their style guides.

In looking back on his career, the octogenarian has a lot to reflect upon. Amid the mistakes and victories transitioning from aimless engineer to newspaper man in charge, he’s not shy about sharing his lessons with anyone who asks. If something is hard, stick with it, he says. Practicing and watching makes perfect. Don’t get comfortable, and always push harder and higher.

In looking back on his career, the octogenarian has a lot to reflect upon. Amid the mistakes and victories transitioning from aimless engineer to newspaper man in charge, he’s not shy about sharing his lessons with anyone who asks. If something is hard, stick with it, he says. Practicing and watching makes perfect. Don’t get comfortable, and always push harder and higher.

“It’s okay to be bad at something for a little while,” Furhmann said. “Imposter syndrome is a common thing.”

It was the strong support system at AAJA that helped him push through that discomfort and grow as a journalist.

“We represent dozens of different ethnicities. Scores of different languages. Some of us are immigrants, some of us were born here. Some of us are from families who’ve been here many generations, some of us are helping immigrant parents on how to navigate around,” Fuhrmann said. “The term ‘Asian Americans,’ it’s overly broad in some ways but it’s the breadth. There’s a strength and a solidarity. ”

IOWA CITY, Iowa — The Asian American Journalist Association had only been in existence for seven years when Henry Fuhrmann, a 31-year old Columbia grad student studying journalism, submitted his first application for membership at the price of $18. What he didn’t know at the moment was how large an impact AAJA would have on his career and relationships in his more than three decades as a member.

The annual conventions in particular played a large social role throughout his development as a journalist.

The annual conventions in particular played a large social role throughout his development as a journalist.

“Any AAJA history that doesn’t include the word ‘fun’ is missing out on some of it,” Fuhrmann said.

For him, mostof the fun came from strong relationships he built at the conventions, such as with the AAJA founders, that lasted for decades.

“It’s a social event but it’s an empowerment event,” Fuhrmann said.

Being in a room with hundreds of other AAPI people was not a common occurrence for Furhmann, whose path to journalism was as winding as it was unpredictable. Coming out of high school, he hadn’t even considered journalism. Instead, he dove headfirst into engineering because he loved math and calculus at the time.

Yet in college, Fuhrmann struggled to find his footing. Disillusioned by the thought of solving engineering problems for the rest of his life, he didn’t know where he belonged. All he knew was that his passions were pointing elsewhere, he said.

“People always think I’m being modest, but this is the literal truth — I was really bad at engineering,” Fuhrmann said.

By a stroke of sheer luck, as he tells it, Fuhrmann met someone who would forever change the trajectory of his career. It was his new roommate that introduced him to the editor of the campus newspaper. That’s when Fuhrmann “kind of got the bug.”

He joined a group of “unwashed” engineering students who got together to put a newspaper in the 1970s. The group spent their days in computer-less rooms cutting out type in columns and sticking them to thin boards. Although the paper “wasn’t that good,” Fuhrmann knew that he had finally found what he was looking for.

After obtaining his bachelors in journalism, his landlord who also happened to be the director of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., helped him land his first job in journalism as a science writer. Once Fuhrmann got his masters in journalism, he was then recruited to Newsday in New York City as a member of the first class of copy editors in Times Mirror’s Minority Editorial Training Program, which focused on training young journalists of color. It was the breakthrough that Fuhrmann needed.

He put his newly gained copy editing skills to use as a copy editor, news editor, and eventually rose to managing editor of the Los Angeles Times in 1990. It was at the prestigious paper where the self-proclaimed late bloomer became close with three of AAJA’s six founders.

He put his newly gained copy editing skills to use as a copy editor, news editor, and eventually rose to managing editor of the Los Angeles Times in 1990. It was at the prestigious paper where the self-proclaimed late bloomer became close with three of AAJA’s six founders.

“It’s a collaborative effort and that to me is the beauty of journalism,” Fuhrmann said. “You are collaborating with other smart, driven, energetic, passionate people.”

Through AAJA, Fuhrmann met Catalyst alumnus Karen Yin, who offered him the opportunity to write a piece in her website, Conscious Style Guide. The platform was devoted to helping writers and editors think critically about language. Fuhrmann penned a piece arguing that the hyphen in “Asian-American” should be removed from style guides because it conveyed that people of color were “not full citizens or fully American.”

Fuhrmann thought “no one would read it,” until his piece began garnering major attention across various digital media and news. It wasn’t long until Buzzfeed, the Associated Press, and The New York Times all decided to unhyphenate “Asian American” in their style guides.

In looking back on his career, the octogenarian has a lot to reflect upon. Amid the mistakes and victories transitioning from aimless engineer to newspaper man in charge, he’s not shy about sharing his lessons with anyone who asks. If something is hard, stick with it, he says. Practicing and watching makes perfect. Don’t get comfortable, and always push harder and higher.

In looking back on his career, the octogenarian has a lot to reflect upon. Amid the mistakes and victories transitioning from aimless engineer to newspaper man in charge, he’s not shy about sharing his lessons with anyone who asks. If something is hard, stick with it, he says. Practicing and watching makes perfect. Don’t get comfortable, and always push harder and higher.

“It’s okay to be bad at something for a little while,” Furhmann said. “Imposter syndrome is a common thing.”

It was the strong support system at AAJA that helped him push through that discomfort and grow as a journalist.

“We represent dozens of different ethnicities. Scores of different languages. Some of us are immigrants, some of us were born here. Some of us are from families who’ve been here many generations, some of us are helping immigrant parents on how to navigate around,” Fuhrmann said. “The term ‘Asian Americans,’ it’s overly broad in some ways but it’s the breadth. There’s a strength and a solidarity. ”